Feature Writing

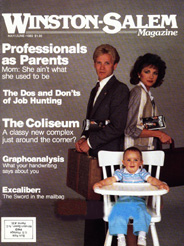

Professionals as Parents

Remember the Cleaver family from “Leave It To Beaver?” Ward spent his time dispersing fatherly wisdom between trips to or from the office while June played most of her scenes from an immaculate kitchen. If Wally and Beaver ever had a babysitter, it was the comedic circumstance upon which the plot turned that week—certainly not part of the household routine.

Aside from plenty of good-humored wholesomeness, the Cleaver family’s single most prominent distinguishing characteristic was normalcy. But today, in nearly two-thirds of the nation’s families, the mother works outside the home. This year, almost half the children born to married mothers will be placed in some form of childcare before they’re a year old so their mothers can return to work.

If the Cleavers can no longer be considered normal, they nevertheless typify for many a cherished notion of the ideal family: “A good provider”—male, of course—married to “a good wife and mother” whose children most willingly adopt their parents’ values. It’s a notion that has seemed to work well—at least in theory—for several generations.

But since the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, when the “Leave It To Beaver” series ran, simple economic necessity has joined with feminism to push many a good wife and mother into the workplace. And while the status of being—or having—a wife who “doesn’t have to work” is still eagerly sought by some, it has become markedly less popular for both practical and personal reasons.

It’s not surprising then, that the contemporary version of ultimate success has evolved into an all-purpose desire to “have it all.” For many married couples, that translates into two brilliant careers, an affluent lifestyle and at least one remarkably well-adjusted child.

In practice, having it all, with its accompanying requirements of somehow getting and managing it all, often produces a reality marked by difficult decisions and compromise. The marriage itself must frequently take a back seat to career and family demands for time, energy and commitment. Even though most couples deliberately defer having children until both careers are established, they’re still concerned about the long-term impact of parenthood on the woman’s career. They’re also concerned that their children must spend a substantial portion of their formative years with someone other than a parent as a primary caretaker.

“We had our concerns about how we’d manage our career and family responsibilities, but so far, everything’s working out just fine,” says pediatrician Marty Wilson, 29, who with her attorney husband Gray Wilson, 33, chose the time immediately following her residency and his promotion to partner to have their son Trover, now nine months old. Early in Marty’s pregnancy, the Wilsons arranged for a fulltime babysitter and housekeeper to work in their home following the three-month break Marty took from work when Trover was born.

“I loved being at home with Trover,” says Marty, “but I didn’t want to get too far behind in my career. My partner had agreed to cover for me for three months, so that’s how long I took.

“I’m sure Trover will grow up with a perspective that’s different from what it might be if I stayed home with him all the time,” she adds. “But as a pediatrician, I don’t expect the fact that he spends a lot of his time with a babysitter to cause any serious problems in his development.”

“Most of my expectations about having a child turned out to be false,” says Gray. “Most of my fears were unfounded. For example, I’d heard horror stories about parents whose social lives came to an end when they had children. But our closest friends already have children, so the biggest difference is that I find the conversations about their children far more interesting now.”

Like the Wilsons, pediatrician Sara Sinal, 39, and her husband Paul Sinal, 39, an attorney, also chose the time immediately following her residency to have their first child, Caroline, who’s now nine. Their second daughter, Katie, followed four years later. Over the years, the Sinal’s child-care experiences have included large day care centers as well as several homecare situations. Currently, a babysitter takes care of both girls at home from the time their school day ends until one of their parents arrives home from work.

“I went back to a full-time schedule two months after Caroline was born and it was awful,” recalls Sara. “I thought I was going to die because I never got to see her. The next time, I took six months. I also work an 80% schedule instead of full-time.”

Sara is now surveying female doctors nationwide to gather information about pregnancy timing, levels of satisfaction about pregnancy timing and the personal and professional circumstances surrounding pregnancies among women doctors. Ultimately, she and her colleagues hope to make the information they gather available to women physicians faced with deciding if and when to have children.

“We expect to find a lot of women who don’t plan on being the primary caretaker of their children,” she notes. “We think we’ll find a new breed of working woman who expects her role to be similar to the father’s traditional role.”

“We thought I should work at least five years to get established before taking time to have a baby,” says attorney Mary Kay Johnson, 34. She and her attorney husband Mike, 38, are the parents of two-year-old Kate and six-week-old Matthew. Mary Kay ended up practicing law for eight years before Kate was born and, after a brief return to work, came home to care for her daughter full-time.

“In thinking about what our lives would be like after the baby was born, I knew things would go smoother if both of us weren’t working,” says Mike. “And my preference was that the mother of my children would bring them up. But I figured for all that to work, Mary Kay had to be happy with it.”

Through a classified ad in the newspaper, the Johnsons hired a full-time babysitter and housekeeper. “When I saw how it was working out with the sitter, I decided it really wasn’t going to be that big a deal,” says Mike. “What it would amount to was that for the first year of her life, Kate would probably be more attached to her sitter than she was to either of us. I didn’t think that would have long-term effects on how she ultimately related to us as her parents.”

“I didn’t ever question that I’d return to work,” says Mary Kay. “I didn’t make the decision to resign until after Kate was born and I’d gone back. I just hadn’t counted on how much I’d miss her.

“There were men at work who assumed from the beginning that I wouldn’t be back because they knew we could afford for me not to work,” she adds. “And there were women at work who seemed to think I was crazy to interrupt my career to have a baby. When I made the decision to quit work and come home, I had a full-time mother say to me, `Good. There should be no working mothers.’ I mean, you can’t win.”

The transition from a career in corporate law to full-time life at home has been difficult for Mary Kay. “I thought I’d come home and have a meticulous home, a spotless child and candlelight dinners for my husband every night,” she says.

“Actually, child care is very time-consuming. Housework is boring and isolating. If you’re going to stay at home, you have to learn how to make yourself happy. That’s been hard for me. My life was geared toward my job and all my friends were through work. It’s a big adjustment I haven’t made completely yet.”

“We both think Mary Kay’s staying home will hurt her career,” says Mike Johnson “How much is still unknown.”

“I miss work and I’m concerned, too, about how long I can stay out of my profession and not do irreparable damage to my career,” adds Mary Kay. “I’d like to find part-time work, but I don’t know how receptive employers are going to be to the idea. And I don’t know how hard it will be to find part-time work that will be satisfying enough to make it worth leaving my children.”

Gwynne Taylor, 34, an architectural historian who operates a part-time consulting business from an office in her home, hires a babysitter to care for two-year-old Winslow anytime she has to work. Husband Dan, 38, is a lawyer. The Taylors also have a housekeeper one day a week.

“I had several years in which I was free to work hard and put all my energy into my career,” says Gwynne. “Since Winslow’s come, I feel no sense of frustration at having given up anything. But if I had to face the future without any professional gratification, I would find it difficult.”

For Phyllis Spruill, a 31-year-old assistant product manager for L’eggs, and her husband James Spruill, 33, a marketing manager for Burroughs Corporation, an unplanned pregnancy provided an upsetting alteration to her career timetable.

“I was ten days away from graduation from MBA school at Chapel Hill and two months away from beginning my new job at L’eggs when my doctor told me I was pregnant. I had wanted to get in at least a year in my career before I even thought about children, and I was thoroughly disgusted when I heard the news. I cried for three days, and Spruill cried with me.”

Once her son was born, Phyllis returned to work as quickly as possible. “Having a baby put corporate life in perspective for me,” she says. “The baby says to me, `Life is not just a job.’ I worked hard to get here and I want to do well. I don’t want people to make concessions for me, but if Allen has a fever, I have to leave. I have no choice.”

For some women, however, the prospect of combining motherhood with a professional career seems too demanding. And by applying impeccable logic that serves them so well in their work to what is essentially an emotional decision, they conclude that the costs of having children outweigh the benefits.

“I know women lawyers who are afraid to stop long enough to have children,” says Paul Sinal. “They know the glut of new lawyers is real and the competition is high. Plus they’ve sacrificed to go through a professional school. They feel they’ve invested so much, they don’t want to take the risk.”

“In the 11 years we’ve been married, Bob and I have never stopped to consider whether we wanted children,” says Carol Mabe, a product manager at L’eggs. “It’s always been a decision we’d make someday in the future. Then, when I went in for a check-up last week, my doctor said, `You’re 36 years old. If you’re going to have a child, you’d better go ahead.’ It really made me stop and think.”

“I know I’d be a wonderful mother, but quite frankly, I’m not sure I’d be strong enough to do it all,” she continues. “I’m in my office at seven in the morning and when I drag in at seven-thirty or eight at night, there are times when I’m too tired to get up out of a chair—much less care for a child.

“Right now I’m on a very fast track. If I stopped to have a baby, I could come back and be a product manager after three months. But it would be the end of the momentum, simply because from that point on, I couldn’t give as much to the job. My child would have to come first, and I’m afraid I’d never be thought of again as the driven professional I am.”

“My father says you can always find a reason not to have a baby,” notes Phyllis Spruill. “There’s never really a time when it won’t interrupt your life, when it won’t make you and your husband have to work harder at pulling things together. You just have to learn to live with the pillows on the sofa askew. You get used to stepping on little bitty cars on the floor. And when you have that child and see him grow and learn and laugh, you know it’s worth it.”

Return to the Winston-Salem Magazine main portfolio page

Let’s Talk About Your Marketing Communications Goals and Challenges!

If you’re looking for help with writing, graphic design and marketing communications and you like the portfolio samples you see here, contact me to schedule a telephone call to explore the possibilities of a collaboration. Of course, there is no cost or obligation for the call.