Chapter

III

How

Pictures Function in Print

Upon

mastering the basic principles of composition, the print journalist is left with

the task of applying them to practical problems of visual communication. “Form

follows function” is one of the most important rules of modern design, and in

determining the compositional form a visual message will take, analysis of

message function is an important first step. According to Click and Baird,

photographs and other illustrations in magazines usually function primarily in

one of five ways. They can (1) attract attention, (2) illustrate a point made in

the text, (3) tell a story with the aid of a caption, (4) tell a story in

sequence with other illustrations and (5) give visual relief to a design.1

Any one picture seldom will be classified exclusively in a single functional

mode. For example, it is possible to attract attention with a picture that also

gives visual relief to a graphic design. The function of a picture influences

all aspects of its final printed form, and until the source clearly understands

exactly what he or she wants a picture to do, it is impossible to determine

which of the rules of visual communication to apply.

Using

illustrations to attract attention

Before

perception of any message can take place at the conscious level, the attention

of the intended receiver of the message must be attracted. Schramm describes the

choice of mass communications to which an individual attends as being determined

by the “Fraction of Selection,” which is:

Expectation

of Reward

_______________________

Effort

Required

The

fraction means simply that one is more likely to select a given communication if

it seems likely to give more reward or require less effort than other

communications.2 As attractors of attention, illustrations often play

an important part in the reader’s unconscious evaluation of the fraction of

selection for a message.

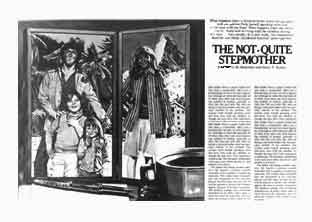

A

picture used to draw attention to an article most often does so by conveying in

visual form the essentials of the verbal message. The illustration in Example 12

functions primarily as an attention-getter for an article titled “The

Not-Quite Stepmother,” which describes a study of the relationship between

divorced men with children and the women with whom those men become romantically

involved.

|

|

|

Example 12.

|

According to the accompanying article, “The not-quite stepmother is

not quite sure where she fits in—and neither is her lover.”3 This

uncertainty is conveyed visually both through picture content and through the

application of the Gestalt principles of proximity and closure.

At

first glance, a reader might perceive the illustration as a snapshot of a

typical family group, but some interesting incongruities prompt further

examination. The man and the children stand before a forest of tropical trees

while the woman is shown in what appears to be a separate snapshot against a

backdrop of snow-covered mountains. Yet the man and the woman are clearly shown

clasping hands as if they were part of the same picture. The physical proximity

of the man to his children expresses their wholeness as a family unit separate

from the woman, but through their similarity of size the man and the woman form

another whole separate from the children. In this way, the illustration

summarizes in visual form the dilemma of the not-quite stepmother: Her

involvement with the man, symbolized by the clasped hands and the similarity of

size, conflicts with the man’s relationship with his children, symbolized by

the incongruent backgrounds and the groupings based on physical proximity. This

visual summary of the article content thus attracts audience attention interest

and conveys the essentials of the article while demanding a relatively small

expenditure of effort.

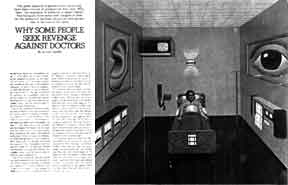

Another

attention-getting illustration accompanies an article titled “Why Some People

Seek Revenge Against Doctors.” (Example 13)

|

|

|

Example 13.

|

The illustration’s power to

attract attention is probably as great or greater than that of the picture in

Example 12, but It also seems probable that the picture compelled at least some

readers to avoid the accompanying article on medical malpractice suits because

of the eerie feeling of isolation the picture evokes. Dember and Earl warn that

the novelty of an attention-getting stimulus should not be so great as to

frighten or repel the observer by its abnormality or by the observer’s

inability to respond appropriately, nor should the stimulus be so complex as to

be beyond the observer’s understanding.4 In Example 13, there is an

overwhelming sense of lifelessness and inactivity in the picture which is

reinforced by the axial balance of visual elements. The use of the color green

for the walls, floor and hospital gown contributes a sense of coldness.

Converging parallel lines in ceiling and floor combine with the relatively small

size of the patient and hospital bed to give the room a cavernous appearance.

If

one reads the article accompanying Example 13, one finds little to justify or

explain the picture content. Certainly, there is some mention of patient

alienation about a third of the way into the article, but other

emotions--notably anger-are more heavily emphasized as characteristic of

patients who bring malpractice suits. Thus the picture attracts attention but,

because of its appearance could repel some readers or perhaps give them an

erroneous impression of article content.

Illustrating

a point made in the text

A

picture used to illustrate a text is intended to enlighten the reader by

clarifying points made in that text. Implicit in that use is the assumption that

words and pictures can complement each other in print communication. This

complementary relationship has as its basis certain differences in the way words

and pictures work. “In speaking,” writes William Bowman in Graphic

Communication, “one says not only what he wants to say but what his

language enables him to say.”5 All languages have inherent

limitations based on the symbols of the language itself and on how those symbols

function. The key to more effective communication in print is understanding the

complementary symbolic functions of verbal and visual languages.

Basically,

symbols work in either of two ways: analogically or digitally. In analogical

systems, the series of symbols is similar in proportions and relations to the

thing, idea or event it represents. Analogical symbol systems are continuous and

without gaps while digital systems are discontinuous and consist of clearly

distinguishable atomic categories that can be defined using other categories

from within the same symbol system. Words almost always function digitally while

pictures usually function as analogs. A word can be defined using other words,

but while pictures can be broken down into discrete elements, it is generally

impossible possible to assign precise definitions to those elements, either in

terms of other visual elements or in terms of words. This seeming lack of

precision should not be equated with an inability to convey meaning, for it is

this characteristic of visual language that enables image-makers to convey

messages that writers cannot.

“Words,”

writes Arthur Koestler, “are a blessing which can turn into a curse. They

crystallize thought; they give articulation and precision to vague images and

hazy intuitions. But a crystal is no longer a fluid.”6 This lack of

fluidity is the primary characteristic of words, or indeed of any digital symbol

system, that restricts the kinds of meaning digital symbols can convey.

“The

greatest power of visual language lies in its immediacy, its spontaneous

evidence,” writes Dondis. “Visually, you see content and form

simultaneously.”7 As Key points out, however, “the total

instantaneous perception of the picture is repressed in favor of certain

details. All the information and meaning are recorded instantly and totally, but

the mind plays what amounts to a trick, permitting only certain details--often

what we want to see or what we can identify with--to filter through into

conscious awareness.”8

Perception

of visual symbols appears, then, to operate on two levels simultaneously. On a

conscious level, the decoding of a visual message is similar to the decoding of

a verbal message in that the visual elements, like words, are sampled across

time, classified and duly recorded. While the eye scans the visual field and

focuses on specific aspects to be entered into conscious awareness, the

unconscious mind accepts and stores a single, instantaneous impression. This

instantaneous communications effect of visual symbol systems is unparalleled in

verbal systems.

Communication

at the unconscious level, while intriguing, is a highly controversial topic.

Little is known about how information stored in the unconscious influences

conscious attitudes and behavior,9 but that the influence is indeed

present is no longer widely disputed. At the conscious level, the observer sees

only what is necessary for meaning,10 even though he or she often

misinterprets and misunderstands messages because of this tendency to assign

meaning immediately. “We cannot say to ourselves, ‘Hold off any

interpretation until you collect all the facts.’ As soon as we experience any

facts, they will be perceived as organized into some sort of meaningful

whole.”11 This organization is referred to by psychologists as

“closure,” and one of the goals of the visual communicator is to control

closure by providing messages with the right amount of complexity for the

audience.

Perhaps

the most common example of text illustration with pictures is the use of

portraits or “mug shots” of people mentioned in the text. Graphs and charts

are also commonly used to clarify text by presenting a visual summary of

relationships, thus exemplifying the visual language at its least equivocal. The

various visual elements in a graph or chart are clearly understood to represent

data and in this sense, such pictures may be said to function digitally in much

the same way words to. Their illustrative value lies in their ability to

function simultaneously as analogs by instantaneously summarizing the

relationships among the digitally presented data as in Example 14, in which

factual information is conveyed at the same time relationships and trends are

communicated. Note also the use of the mug shot for illustration.

|

|

|

Example 14. Factual information is conveyed at the same

time relationships and trends are communicated.

|

Telling

a story with a single picture

In

discussing the use of a single picture to tell a story, Click and Baird write

that “the possibility of a single photograph telling a story or making a point

without the aid of any words is so rare as to merit elimination from the list of

possibilities.”12 Implicit in this statement is the authors’

ill-conceived denial of the very real tendency of all pictures to convey a

message of some kind to anyone who perceives them. Indeed, by defining the word

“story” rather broadly, one can safely assert that every picture tells a

story, provided the picture’s perceiver believes the picture to be potentially

meaningful.

According

to Gordon, “The conscious attempt to create a seemingly ‘sensible’ field

around ourselves is probably one of the strongest of our drives.”13

Because of this need for meaning, an un-interpreted picture creates a conflict

in a perceiver that can be resolved only through his or her interpreting that

picture. Ideally, the perceiver’s interpretation of a picture corresponds as

closely as possible with the meaning intended by the source, but if a perceiver

misunderstands the sender’s intentions, according to Gordon,

the

perceiver usually resolves his confusion by searching into his own

predispositions to find hidden meanings. He thus introduces his own opinions,

prejudices, attitudes and beliefs into an ambiguous field, with the result that

he believes that he has cleared up his confusion. He has not. He has simply

succeeded in eliminating the psychological tension that in-variably results when

an individual faces chaos in his perceptions.14

It

is important to note Gordon’s reference to “an ambiguous field,” for the

breadth of audience Interpretation of any message is determined primarily by the

degree of ambiguity in that message. Because visual communication is inherently

more equivocal than verbal communication, print journalists can effectively

narrow the range of interpretations for any one picture by providing their

audiences with a supporting verbal message, usually in the form of a caption.

The extent to which captions can influence picture interpretation was explored

during the 1950s by Kerrick who presented her conclusions in an article for Journalism

Quarterly. Kerrick’s research suggested that a caption can modify picture

interpretation in ways that can be predicted by the writer of the caption, but a

caption that is in obvious conflict with picture content will most often be

rejected.15 Thus, as Kerrick’s findings indicate, words can guide

picture interpretation only so long as their message appears to be consistent

with the picture’s message.

In

some oases, a certain degree of ambiguity may be desirable because an ambiguous

picture often attracts the attention of the observer and encourages his or her

participation in the communications process through filling in blurred or

missing parts. According to John Cataldo, “Distortions are designed to attract

the attention of the reader and invite his participation, much in the same

manner that a tipped picture on a wall invites the viewer to reestablish its

balance.”16 Thus, if the source wants to encourage reader

participation, perhaps at the expense of clarity and specificity, then he or she

may select a relatively abstract or ambiguous photograph or drawing as in

Example 15, wherein lack of detail, particularly in the family grouping,

encourages reader identification with characters in the accompanying story.

|

|

|

Example 15. Lack of detail encourages reader

identification with characters in the story.

|

The

calculated use of ambiguity in visual communication is not to be confused with

the ambiguity that results from the source’s inability to express visual ideas

clearly. Similarly, ambiguity is not to be equated with lack of detail. In

conveying factual information, the mechanical exactness of a photograph may seem

ideal, but often a drawing can convey meaning more clearly by presenting only

relevant information.17 It was found, for example,, that realistic

photographs of organs did not help students understand a medical lecture while

cartoon-like drawings helped significantly.18 Often it is useful to

use both detailed and simple illustrations. In Example 16, photographs show in

detail a project’s final appearance while drawings clearly demonstrate how it

is to be constructed.

|

|

|

Example 16. Detailed photographs show final appearance of

a project while drawings show essentials only.

|

Telling

a story in sequence with other pictures

Although

a single picture can tell a complete story, its communicative potential is often

enhanced when it becomes part of a picture sequence. Perhaps the most common

sequential use of pictures is for how-to articles in which a step-by-step

process is explained in word and picture form as in Example 17.

|

|

|

Example 17. A picture sequence shows a step-by-step task.

|

Pictures in

sequence also help tell the before-after story of a Texas town’s renovation in

Example 18, while in Example 19, a series of three pictures showing a sunrise

conveys a symbol of optimism in visual form.

|

|

|

Example 18. A before-after sequence.

|

|

|

|

Example 19. A sequence of pictures conveys a sunrise.

|

As these examples show, an

individual picture in a sequence has a better chance of being interpreted as the

source meant it to be than does that same picture appearing alone because of the

tendency of other pictures in the sequence to help clarify the source’s

intentions.

Giving

visual relief to a design

“The

weakest reason for using illustrations,” say Click and Baird, “is for

decoration, but there are instances when this motive alone provides adequate

justification.” 19 Masses of type can be forbidding to some readers, so by

breaking up solid type areas with appropriate illustrations, editors make

articles seem more inviting. Illustrations functioning as decoration need not

convey actual information, but they should appear to be in harmony with the

message as a whole. The recipe page in Example 20 is decorated with drawings

that contribute to the communications effort by making the page more attractive.

The informative function of such pictures, however, is minimal.

|

|

|

Example 20. Drawings decorate the page and provide visual

relief but convey little information.

|

Summary

How

the basic principles of visual communication are to be applied depends primarily

on the specific functional goals of the message. Pictures most often function

primarily to attract attention, to illustrate a point made in the text, to tell

a story with the aid of a caption, to tell a story in sequence with other

pictures or to give visual relief to a design.

Notes

from Chapter III

1J.

W. Click and Russell N. Baird, Magazine Editing and Production (Dubuque,

IA: Wm. C. Brown Company, 1979), p. 151.

2Wilbur

Schramm, ed., The Process and Effects of Mass Communication (Urbana, IL:

University of Illinois Press, 1961), p. 19.

3Kristine

M. Rosenthal and Harry K. Keshet, “The Not-Quite Stepmother,” Psychology

Today, 12, No. 2 (July 1978), p. 83.

4Vernon,

p. 71.

5William

J. Bowman, Graphic Communication (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.,

1968), p. 3.

6Arthur

Koestler, The Act of Creation (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1969), p.

173.

7Dondis,

p. 106.

8Wilson

Bryan Key, Subliminal Seduction (New York: Signet, 1973), p. 52.

9Ibid.,

p. 61.

10Carolyn

M. Bloomer, Principles of Visual Perception (New York: Van Nostrand

Reinhold Company, 1976), p. 44.

11David

Krech and Richard S. Crutchfield, “Perceiving the World,” Theory and

Problems of Social Psychology (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1948), p. 120.

12Click

and Baird, p. 155.

13Gordon,

p. 204.

14Ibid.,

p. 218.

15Jean

S. Kerrick, “The Influence of Captions on Picture Interpretation,” Journalism

Quarterly, 32:177-182 (1955), p. 182.

16John

W. Cataldo, Graphic Design and Visual Communication (Scranton, PA:

International Textbook Company, 1966), p. 42.

17Arnheim,

p. 157.

18John

M. Kennedy, A Psychology of Picture Perception (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Publishers, 1974), p. 145.

19Click

and Baird, p. 155.

© 1980 by Gretchen Kerry

Nesbit