Chapter

II

The

Basics of Visual Communication

For

the print journalist, the ability to create a meaningful visual

message depends in part on learning about basic compositional

elements and their interactions. The basic elements of a visual

message are point, line and shape. These elements generally have

characteristic visual weight and direction. To control weight and

direction effectively, visual communicators often adhere to

principles of perceptual organization first described by the Gestalt

psychologists. Borrowing from the literacy analogy, a basic

knowledge of these elements of composition and their interactions is

comparable to knowing the alphabet, a few simple words and some

elementary rules of syntax.

Point,

line and shape

The

point is the simplest, irreducibly minimum unit of visual

communication. According to Dale G. Cleaver, “Line may be thought

of as the path of a moving point, as the edge of a flat shape, as

the axis (dominant direction) of a shape, or as the contour of a

solid object.”1 A shape is an area or plane with

distinguishable boundaries and, as Cleaver explains, “Shape, like

line, may have many personalities: rigid, flexible precise,

uncertain, calm, active, awkward, or graceful.”2

The

three basic shapes are the square, associated with dullness, honesty

and straightness; the triangle, associated with action, conflict and

tension; and the circle, associated with endlessness, warmth and

protection.

In

composing a picture or designing a page, it is generally desirable

to strive for balance. Equilibrium is man’s firmest and strongest

visual reference3 and, according to Rudolf Arnheim,

“man strives for equilibrium in all phases of his physical and

mental existence.”4 The various compositional elements

have characteristic visual weights determined primarily by their

size, tone, shape, color, location on the visual axes and subject

matter. These relationships are summarized in Table 1 and

illustrated by the author in Figures 1 through 6.

|

|

Heavy

|

Light

|

|

size

|

large

|

small

|

|

tone

|

dark

|

light

|

|

shape

|

regular

|

irregular

|

|

color

|

warm

|

cold

|

|

location

|

off

axis

|

on

axis

|

|

subject

|

high

interest

|

low

interest

|

|

Table

1. Determinants of Visual Weight

|

|

|

|

Figure

1. Size as a determinant of visual weight

|

|

|

|

Figure

2. Tone as a determinant of visual weight

|

|

|

|

Figure

3. Shape as a determinant of visual weight

|

|

|

|

Figure

4. Color as a determinant of visual weight

|

|

|

|

Figure

5. Location as a determinant of visual weight

|

|

|

|

Figure

6. Subject as a determinant of visual weight

|

It should be

emphasized that these are relationships, not absolutes, and that the

various factors can interact. For example, a large visual element

may be balanced against a high-interest subject, or an element

placed on one of the visual axes may be balanced by a warm-colored

off-axis element. In any case, unless the specific effect of

imbalance is desired, compositions should ultimately resolve into a

balance.

Cleaver

writes:

Balance

may be axial, that is, organized on either side of an actual

or implied axis that acts as a fulcrum, or central, that is,

radiating from or converging upon an actual or implied central

point. Axial balance may be obvious (symmetrical), having

very similar or identical elements on either side of the axis, or it

may be occult (asymmetrical), having an equilibrium of

elements that are dissimilar in size or shape. Central balance may

also be obvious with similar elements in equilibrium around a

center, or occult, using dissimilar elements.5

Some

of the most important techniques of balance are illustrated in

Figures 7 through 10 (adapted from Cleaver) and Examples 1 through

3, taken from recent issues of various popular magazines.

|

|

|

Figure 7. Axial balance achieved symmetrically

|

|

|

|

Figure 8. Axial balance achieved asymmetrically

|

|

|

|

Figure 9. Central balance achieved symmetrically

|

|

|

|

Figure 10. Central balance achieved asymmetrically

|

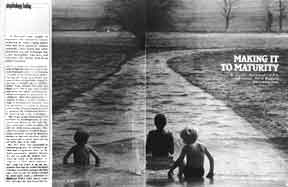

In Example

1, notice how each visual element on the left page of the spread is

symmetrically balanced against an element on the facing page.

Example 2 achieves asymmetrical balance with the visual weight of

the two children near the center balanced against that of the boy to

the left whose weight is increased by his distance from the vertical

axis. Visual elements are balanced around a central figure in

Example 3.

|

|

|

Example 1. Symmetrical axial balance.

|

|

|

|

Example 2. Asymmetrical axial balance.

|

|

|

|

Example 3. Central Balance.

|

Movement

According

to art historian and theorist E. H. Gombrich, movement always helps

confirm or refute provisional interpretations or anticipations of

visual messages and, for that reason, reading of static images is

prone to large variations and contradictory interpretations.6

The print journalist is confined to static images and, as a

consequence, confronts problems similar to those described by

Gombrich. It is possible, however, to give the impression of

movement in a static image. As Cleaver explains, “To suggest or

emphasize movement, …line may be used in at least two ways: It may

represent or suggest things we know are capable of motion, such as

rippling waves, or it may imply motion by its form or by its

relation to other lines.”7 Shapes, too, can have

characteristic motions. Cleaver writes, “Static shapes maintain a

rigid equilibrium within themselves and with their environment.

Shapes become more dynamic as they draw our attention in a specific

direction.”8

Besides

the implied physical activity of visual elements, the term

“movement” is also used to describe the activity of the

viewer’s eye as it is affected by those visual elements. According

to Dondis, the visual directions have strong associative meanings.

Horizontal-vertical movements are associated with well-being and

maneuverability because of man’s overriding need for equilibrium.

Diagonal movements imply instability, and are provoking and

threatening. Curved movements give the feeling of encompassment,

repetition and warmth.9 Again, it must be noted that

these phenomena are not absolutes, but are very much related to the

visual contexts in which they appear. Properties of movement are

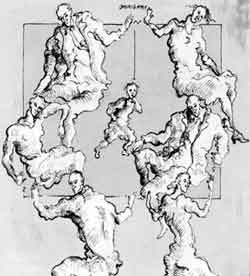

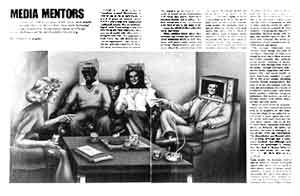

illustrated in Examples 4 through 7. In Example 4, dotted lines

suggest water’s movement. Parallel lines appear to move out of

alignment because of their relation to the diagonal lines. The

strong horizontal line created by the two snorkelers in Example 5

conveys rest and stability while the diagonal lines of the man’s

body and the net in Example 6 suggest activity and stress. In

Example 7, circular eye movements from face to fact and to objects

on the table convey encompassment and warmth.

|

|

|

|

Example 4. Dotted lines suggest water’s movement.

Parallel lines appear to move out of alignment because of

their relation to the diagonals.

|

|

|

|

Example 5. Horizontal-vertical eye movements convey

rest, stability.

|

|

|

|

Example 6. Diagonal eye movements convey activity,

stress.

|

|

|

|

Example 7. Circular eye movements convey

encompassment, warmth.

|

Gestalt

principles of organization

In

addition to being influenced by the inherent visual weight and

direction of visual elements in a composition, the viewer’s

response is influenced according to innate tendencies of visual

organization first described by the Gestalt psychologists. In

explaining Gestalt theory, psychologist M. D. Vernon writes,

“There exists an inherent tendency to organize what is perceived

into configurations…. Organization takes place in

accordance with the Law of Prägnanz, (‘goodness’), which

states that configurations tend to appear as clear, impressive and

stable as possible.”10 To this definition, Arnheim

adds, “Any stimulus pattern tends to be seen in such a way that

the resulting structure is as simple as the given conditions

permit.”11 People simplify visual stimuli in several

predictable ways. The Gestalt principles are descriptive of these

common ways of organizing, The four most important principles of

visual organization are those of similarity, proximity, closure and

good continuation.

According

to the principle of similarity, when two elements resemble each

other in some way, such as size, weight, form, color or structure,

the similarity will create a visual attraction across intervening

space, The principle of proximity is defined as a tendency to see

elements that are close together as belonging together. According to

the principle of closure, there is a tendency to create a unified

mass through the association of isolated elements and to shape

optical units into closed, compact wholes whenever possible. The

principle of good continuation is described as a tendency to see

lines and edges as uninterruptedly as possible, and when there is a

choice between several possible continuations of lines, hues, tonal

values or chroma, to prefer spontaneously the one which carries the

intrinsic structure most consistently. These four basic Gestalt

principles are illustrated by the author in Figures 14 through 19

and in Examples 8 through 11.

|

|

|

Figure 14. Similarity of Shape

|

|

|

|

Figure 15. Similarity of size

|

|

|

|

Figure 16. Similarity of color

|

|

|

|

Figure 17. Proximity

|

|

|

|

These lines tend to be organized into figures.

|

|

Figure 18. Closure

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is seen

|

as this

|

not this.

|

|

Figure 19. Good continuation

|

|

|

|

|

|

Example 8. Similarity of

shape

|

Because of their similarity of shape,

the three candles in Example 8 tend to be grouped together.

|

|

|

Example 9. Proximity.

|

In

Example 9, the proximity of the two upper pictures makes readers

tend to pair them while seeing the picture to the lower right of the

page as unrelated to the other two.

|

|

|

Example 10. Closure.

|

|

|

|

Example 11.

|

Closure makes readers see the

areas defined by dotted lines in Example 10 as complete forms while

good continuation makes the pictures in Example 11 appear to be

lying on top of each other rather than appearing oddly shaped.

Summary

The

basic elements of a visual message are point, line and shape. These

elements generally have a characteristic visual weight determined by

size, tone., shape, color,, location on the visual axes and subject

matter, a visual direction determined by shape and subject, and a

characteristic visual movement determined by shape and eye motions.

To control weight and direction effectively, visual communicators

often adhere to various principles of organization first described

by Gestalt psychologists. The most important of these principles are

those of similarity, proximity, closure and good continuation.

Notes

from Chapter II

1Dale

G. Cleaver, Art: An Introduction (New York: Harcourt Brace

Jovanovich, Inc., 1972), p. 4.

2Ibid.,

p. 8.

3Ibid.,

p. 22.

4Rudolf

Arnheim, Art and Visual Perception (Berkeley, CA: University

of California Press, 1974), p. 36.

5Cleaver,

pp. 20-21.

6E.

H. Gombrich, Julian Hochberg and Max Black, Art, Perception and

Reality (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972),

p. 32.

7Cleaver,

p. 6.

8Ibid.,

p. 10.

9Dondis,

pp. 46-47.

10M.

D. Vernon, Perception Through Experience (London: Methuen and

Company, Ltd., 1970), p. 35.

11Arnheim,

p. 53.

© 1980 by Gretchen Kerry

Nesbit